Rum Diplomacy: Napoleon's Impact on Rum

part 4 of a sojourn through paris with rum

Paris: The Unlikely Mecca of Rum Connoisseurs

I step out of the Ritz, disappointed but no less convinced that Paris is currently the epicenter for rum appreciation. I understand that the Ritz Paris was always intended to appeal to monied foreigners. If the holidaymakers are thirsty, let them drink margaritas. I have already experienced two establishments in Paris that specialize solely in rum and appear to be thriving.

Why France Gives a Damn About Rum

Why is rum so well received in France? It may be because the rum-producing islands of Martinique, Guadeloupe, and Reunion (Indian Ocean) are considered part of modern France and not forgotten colonies. The rums of Martinique have the Appellation D’Origine Contrôlée (AOC) recognition. AOC in France refers to an agricultural product whose stages of production and processing are carried out in a defined geographical area – the terroir – and using recognized and traditional methods. The AOC has roots going back to 1411, tied to the production of blue Roquefort cheese. In 1936, Cognac and Cote du Rhone wine were awarded the AOC designation. After WWII, the French introduced the AOC to more products, including meat, lavender oil, lentils, honey, and butter. There are over 300 wines and 40 cheeses that have the AOC distinction. In spirits, there are only four AOC categories: Armagnac, Calvados, Cognac, and Martinique Rhum agricole. The French are rightfully proud of their food, wine, and spirits status worldwide. For Martinique Rhum agricole to be on the short list of AOC spirits is no small honor. The French embrace Martinique rum as a French product, just like they embrace Champagne as distinctly French.

Napoleon's Pillar and His Unintended Legacy on Rum

It would be a 25-minute walk from Place Vendome to my next rum boutique, Excellence Rhum, in the Saint Germain neighborhood. Standing in the center of the chic square before me is the Column Vendome, which Napoléon had erected in 1806 to commemorate his 1805 victory at Austerlitz. Napoléon not only saved France, wreaked havoc on Europe, and transformed the boundaries of North America but also unintentionally left an indelible mark on rum.

I walked a few blocks past Maxim’s, an iconic early 20th-century restaurant, to the Place de la Concorde, the rally center of the French Revolution. France was in chaos for a decade after the Revolution began in 1789. Mobs would execute Marie Antoinette, Robespierre, and over a thousand others by guillotine on this site.

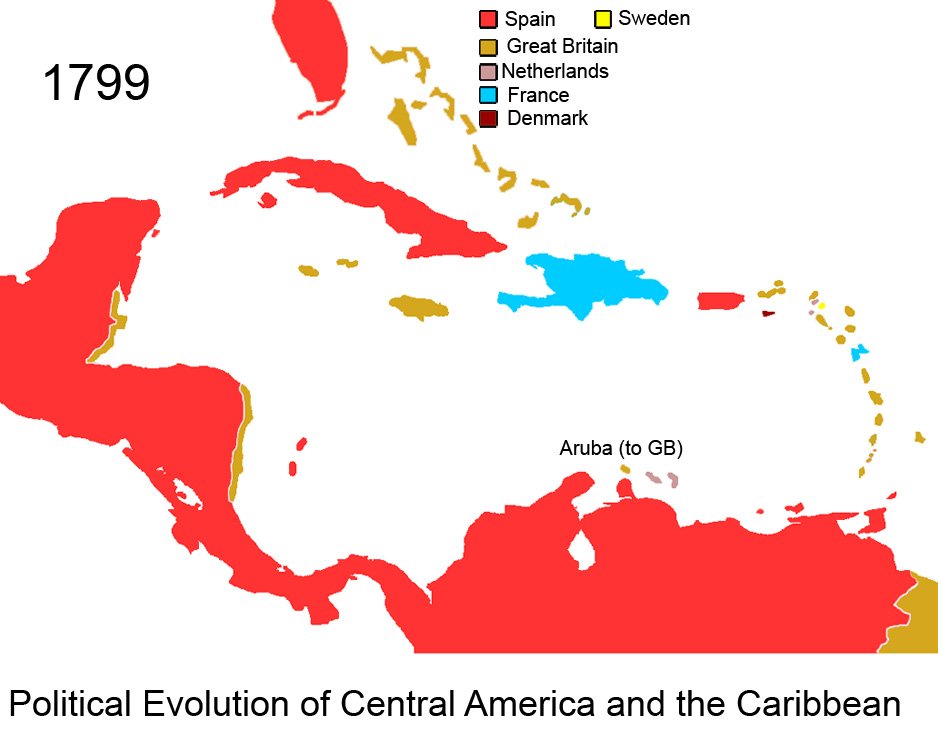

Once the Reign of Terror subsided in 1794 and amidst the spirit of “Liberté, Egalité, Fraternité,” the Revolutionary-French government abolished slavery in French colonies. By 1799 Napoléon Bonaparte had taken power in France. His muse and wife, Josephine, was a white Creole born and raised to a sugar plantation-owning family in Martinique. In 1802 Napoléon officially reinstated slavery. Saint-Dominque (modern Haiti), which had revolted since 1791, would win independence by 1804.

How Napoleon Screwed Over the Caribbean

In just over a decade, Napoléon would upend the colonial system France had established during the previous two centuries, bringing a demise to the importance of the West Indies to France’s well-being. With Haiti lost, Napoléon turned his back on the Louisiana territory as he realized it would be too hard to control the large swath of North America, which he had recently won from battles with Spain in Europe. He sold Louisiana, which extended from New Orleans up the Mississippi River and as far west as Montana, to the United States to fund further European campaigns.

Sugar Beets Over Slavery: Napoleon's Economic Warfare

Sugar became scarce with the British blockading French harbors during the Napoléonic Wars between 1803 and 1815. In the spirit of national defense, Napoléon helped fund and speed up the technology to retrieve usable sugar from the sugar beet grown in Europe. In 1813, farmers and scientists succeeded, and Napoléon banned sugar imports to France. The colonies started in 1635 to satisfy Europe’s craving for sugar were stripped of their primary marketplace. In 1815, Napoléon supported abolishing slavery only after he was confident that France’s supply of sugar would not be disrupted. Martinique’s enslaved people were never freed in 1794 as the island's white population invited the British to occupy and maintain slavery, preserving their business interests. Emancipation would not come until 1848.

This era of conquest, slavery, and land swapping inspired the invention of the board game La Conquête du Monde (The Conquest of the World) by French filmmaker Albert Lamorisse in 1957. Parker Brothers later acquired it in 1959, and the game became widely known as Risk. The game centers around global domination, where players control different armies represented by colored tokens and aim to conquer territories on a world map. However, despite having six continents and 42 territories, the islands of the Caribbean are conspicuously absent from the board. While players can vie for control over regions like Iceland, Ukraine, and Alaska, the West Indies are notably left out, which seems ironic considering the game is themed around the Napoléonic era—a period strongly connected to the Caribbean. Or perhaps it is spot on as Lamorisse, the designer, was aware of Napoléon's apathy towards the region.

The Caribbean: A Melting Pot Shaped by Sugar and Suffering

The Caribbean holds historical significance as one of the earliest regions where so many people of diverse cultures intersected on such a large scale. European explorers initially came seeking gold and new trade routes to China, but they stayed to exploit the region's rich resources, producing cotton, tobacco, and sugar. This led to the importation of forced labor from Africa and indentured servants from India, Indonesia, China, and the Middle East, nearly eradicating the indigenous Carib and Arawak populations.

Economic interests were pivotal in territorial exchanges in the colonial era. The Dutch, recognizing the value of Dutch Guiana (modern- day Surinam), relinquished control of New Netherland (modern-day New York) to the British in the Treaty of Breda (1667). Similarly, the French chose to retain their lucrative sugar-rich islands of Martinique and Guadalupe, ceding Quebec to the British under the Treaty of Paris (1763). These decisions were primarily driven by the profitability of the sugar trade, which flourished in the Caribbean during that time, shaping the region's history for centuries. Napoléon's actions would change all that, and its consequences would reverberate for centuries after his short-lived grip on the world.

Martinique Rhum Agricole: Napoleon's Accidental Gift to Rum

The temporary lack of markets for Martinique sugar led to the tinkering of making rum from freshly pressed sugarcane juice without bothering to make sugar and the byproduct molasses, the traditional base ingredient. Martinique and its neighbor Guadalupe still made sugar for other markets and produced molasses-based rum for export. For local consumption, islanders tended to drink rum made from cane juice, with distinctly vegetal grassy characteristics. Martinique never stopped making rum with molasses, but the Martinique Rhum agricole we enjoy today was, in part, an unintentional collateral gift to rum when Napoléon blocked Martinique of its primary market and left the island to fend for itself.

This one action by Napoléon, banning imported sugar, didn’t single-handedly start the course for Martinique Rhum agricole to come into being, but it played the primary role. At that time, French people preferred Barbados and Jamaican rums to that of Martinique. When the Revolutionary government of France banned slavery, the white planters of Martinique allowed the British to temporarily take control of the islands and preserve slavery. Sugar production did not end, and in fact, it would grow dramatically over the next century. The occupation by the British led to some sharing of knowledge and improvement for the rum of Martinique.

By 1902, Martinique was the world’s largest rum exporter, primarily molasses-based. The eruption of Mount Pelée in 1902 destroyed the capital rum-making city of Saint-Pierre, killing 30,000 people and wiping out dozens of distilleries. Amidst the mourning for life, Martinique planters not in the destruction zone of the explosion saw this as an opportunity to enter the rum business with upgraded and modernized rum-producing facilities. Napoléon also helped spur the development of the continuous still, which could distill ten times faster than the standard pot still. While still nascent, the column still was being widely adopted. French people sometimes refer to rum that is not “agricole” as “industrial.” It is meant as a slight, of course. Still, the intended slight is misinformed as “rhum agricole” represented the use of the latest technologies of the Industrial Era, and the product could have been aptly named “Martinique Rhum industrial.”

How Wars and Bad Harvests Made France Thirsty for Rum

In the coming century, France would have periods of poor grape harvests, and the demand for Martinique rum would increase to satisfy the country's thirst for alcohol. During WWI and WWII, Martinique had significant spikes in exports of its rum, and rum became a staple in the palette of France. In 1946 after WWII, Martinique and Guadeloupe became Oversea Departments of France. They have the same status as mainland France’s regions and departments. It wasn’t until around 1970 that the production of rhum agricole outpaced the production of molasses-based rum, partly because planters had essentially given up on sugar production by then. In 1974 Martinique's neighbor to the west, Mexico, created a Geographic Indication (GI) for Tequila. Coincidently, rum producers on the island began seeking the French AOC distinction for Martinique rum in 1975. In 1996 it was granted.

Author Owen Hyland founded Faraday West Indies Rum and lives in New Hampshire.