RUM THROUGH THE TULIPS: AMSTERDAM'S CARIBBEAN BAR, RUM BARREL

Part 1: The Routes of Rum in Amsterdam’s Streets

FROM FANCY FRANCE TO HUMBLE HOLLAND

My rum journey through Europe continued in Amsterdam. After a day of business meetings, I met up with my sister, who arrived by train from Paris. We planned to meet with relatives in The Hague and revisit the house where our mother grew up. But first, the itinerary for the evening included a visit to a bar named Rum Barrel, followed by the classic meal of rijsttafel (rice table), an elaborate Dutch-Indonesian spread of small, flavorful dishes served with rice.

The Netherlands may not be the first European country that comes to mind when one thinks of rum. Yet, the Dutch played a central role in the origin of rum, and today, Amsterdam is a significant hub of the global rum trade. While Caribbean rum typically conjures images of colonial powers like the British, French, and Spanish in Barbados, Martinique, and Hispaniola, respectively, we (rum enthusiasts) don’t talk about rums from former Dutch colonies of Suriname, Aruba, or Saint Martin. We also don't hear about Portuguese rums, yet the Portuguese have distilled sugarcane spirits in Madeira, off the west coast of Africa, and Brazil since the 1500s. Join us as we unravel the forgotten pages of history and delve into how the Dutch played a pivotal yet unrecognized role in shaping the story of rum.

I was curious to see if Rum Barrel would weave in the Dutch narrative and relationship to rum the way the bars in Paris we visited showcased strong connections to rums from Martinique, Guadeloupe, and Reunion. Dirty Dick in Montmartre had craftily taken a kitschy American phenomenon, tiki, and put a distinctively French twist on it by highlighting the Gauguin-styled murals of French Polynesia. Bar 1802 in the Latin Quarter recreated a colonial-era Paris salon and laced tales of the Black experience in Paris and the French empire during the early 19th century. The bartenders were skilled, knowledgeable, and eager to nerd out on rum.

Clues to the Dutch connection to rum can be seen in the city, and they are in plain sight but subtle and easily overlooked. The Dutch don’t seem to reference their colonial history to the outside world as much as the British and the French. No Arc de Triumph or Trafalgar Square commemorates their armies and navies. Yet, in the 1600s, the Netherlands had an empire exceeding England's and France’s, and rum directly resulted from Dutch colonial exploits. A city tour will reveal Amsterdam’s modern connection to the past.

Evolution of Elegance: Unveiling 17th-Century Canalside Heritage and Modern Dutch Identity

We ordered an Uber outside our hotel in the Weesperbuurt, just at the eastern edge of the three main canals of Amsterdam-Centrum. We were headed for Javastraat (Java Street) in Indische Buurt (Indies Neighborhood), the once-rough, now-hip district in East Amsterdam. A noticeable architectural metamorphosis unfolded as we glided alongside the picturesque canals lined by budding trees. The charming 17th-century canal houses, with their slender silhouettes, towering heights, gabled roofs, and intricate facades, gave way to much larger, unadorned brick buildings. This architectural transformation symbolized a departure from the historical grace of bygone eras to a modern, straightforward, unfussy style, mirroring a similar transformation in the character of the Dutch people.

The route traced the Amstel River, passing the Tropenmuseum before turning onto Borneostraat and Javastraat. Rum Barrel is in the heart of the Indische Buurt. It is on the ground floor of a 1900s five-story brick building with oversized windows flanked by nearly identical buildings. The surroundings exuded a uniformity that stretched for blocks, with broad streets accommodating bicycle parking and outdoor seating. Picnic tables, sheltered under a large orange umbrella, adorned the sidewalk in front.

RUM BARREL: A FUSION OF AESTHETICS in INDICSHE BUURT

Stepping inside Rum Barrel revealed a fusion of aesthetics, with batik-designed tiles and rattan bar stools subtly hinting at Indonesian influences. Above the bar, industrial light bulbs nestled in empty rum bottles cast a warm glow. The wall behind the bar showcased an array of rum bottles, neatly arranged in square shelves with backlighting, accompanied by draping plants. A large Havana Club logo adorned one wall, while another had a mural of urban Cuba. While the place had a general “island vibe,” it was explicitly Spanish, with no hint of the Dutch connection to the West Indies or rum. Instead, the ambiance mirrored the carefree spirit of a young backpacker's global adventures, brought back to life within the bar's inviting walls.

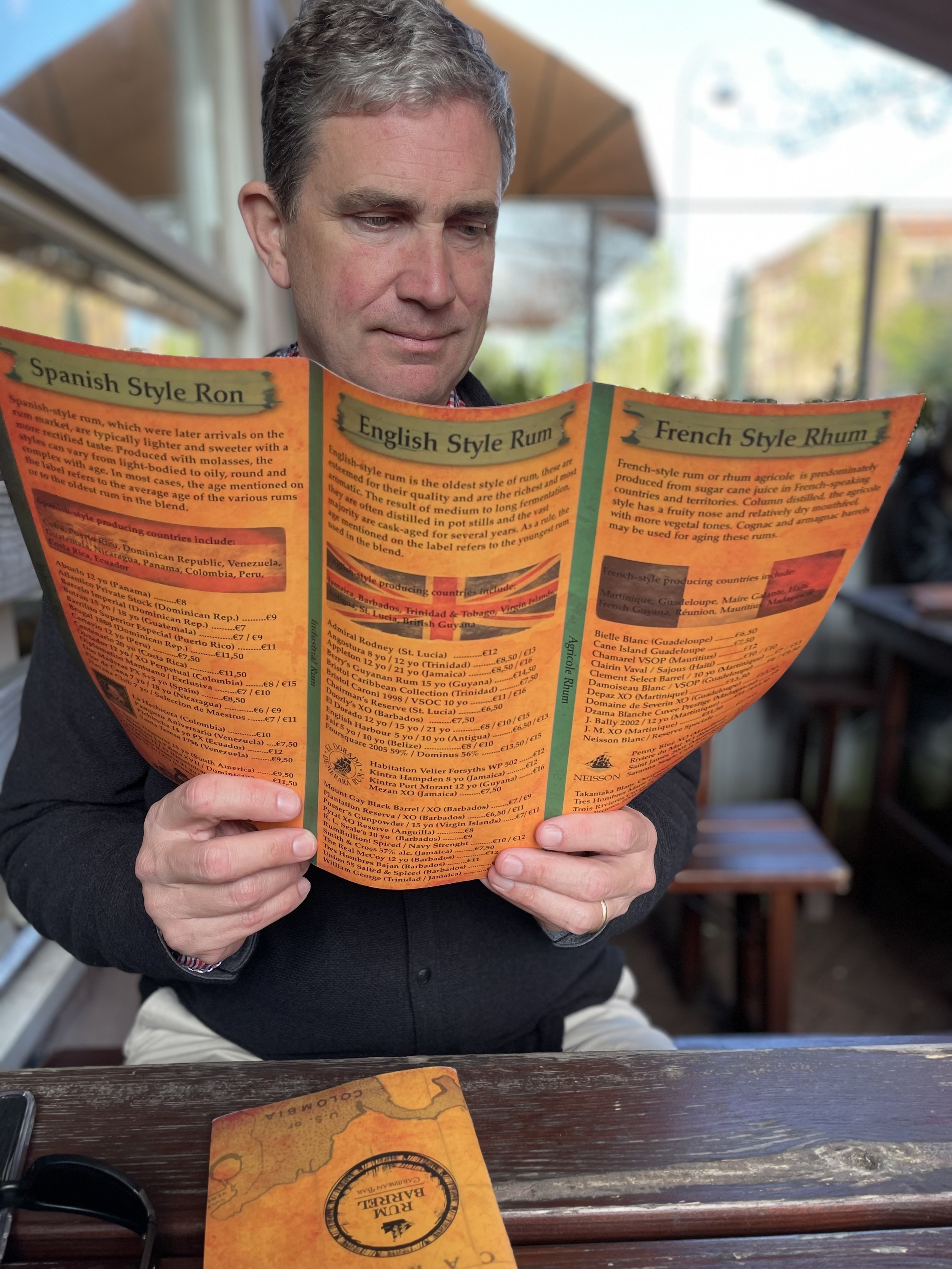

We chose to sit outside in the courtyard to enjoy the mild spring air and the lengthening evening sunlight. The 3-fold laminated menu was comprehensive. None of this, “aroma is our guide to creating your cocktail,” or “the rum selection is always rotating, so we can’t list them all.” This was The Netherlands, not France. Pragmatism over existentialism. There were 28 named cocktails to choose from and over 60 sipping rums divided into British, French, and Spanish categories, with descriptions of the distinguishing characteristics of those styles of rums. This unpretentiousness contrasted with the high-concept ambiance of trendier Parisian counterparts. The founders of Rum Barrell created something cool; they know it and spell it out for you to enjoy.

A HEMINGWAY DAIQUIRI: THANK YOU

The drink menu unfolded with various options, from classic daiquiris to tiki standards like Mai Tais and Zombies. A nod to Ernest in the form of a Hemingway daiquiri caught our attention. (This was the cocktail I failed to find at the Bar Hemmingway in the Ritz Paris.) The inclusivity of the menu extended beyond rum purism, with tequila and whiskey concoctions for those with different preferences. I also noticed bottles of Kettle One and Tanqueray behind the bar. We both chose the Hemingway daiquiri, a departure from the standard but a welcomed deviation.

As we waited for our cocktails, I glanced at the food menu. It leaned toward Latin American cuisine, featuring chorizo croquettes and chicken pineapple quesadillas. There was no acknowledgment of the Netherlands Antilles, no roti from Suriname, or goat stew from Bonaire.

Our drinks arrived, and they did not disappoint. When I asked the waiter what rum was used in the cocktails, he replied he didn’t know but went to the bartender and cheerfully returned with the answer. They had a citrusy zing to begin, balanced by the sweetness of the maraschino liqueur. The slightly bitter grapefruit clamped down on the sourness of the lime, making it a more subtle and deeper-textured cocktail than a standard daiquiri. It had a clean base of Havana Club and Wray & Nephew rums, balancing mellow and funk.

DUTCH COLONIAL HISTORY in PLAIN SIGHT

As we enjoyed our cocktails, I unfolded a tourist map on the picnic table, and my attention was drawn to the intriguing street names surrounding us—Burma, Borneo, and Sumatra. This sparked a curiosity to explore further, leading me to discover an obvious tapestry of Dutch colonial history intentionally woven into the street plan of Amsterdam.

Route Traveled

To the west of our current location, beyond the canal ring from where we started, lay the Westindiche Buurt (West Indies Neighborhood). Between the leafy stretches of Rembrandt Park and Vondel Park, this area has street names of Suriname, Aruba, and Curaçao, a region of the New World the Dutch began colonizing in 1616. To the north, the streets bear the names of pivotal figures—Henry Hudson, Peter Stuyvesant, and the Van Rensselaer family—who played crucial roles in forming New Netherland. That colony, founded in 1614, stretched from modern-day Connecticut to Delaware, with New York State and Manhattan at its core. Between the two Indies neighborhoods and further south, I noticed the Transvaalbuurt (Transvaal Neighborhood), with streets named Afrikaner and Boer, recalling the Cape Colony (established 1652) in modern-day South Africa.

THE DUTCH GOLDEN AGE and the ROUTES of RUM

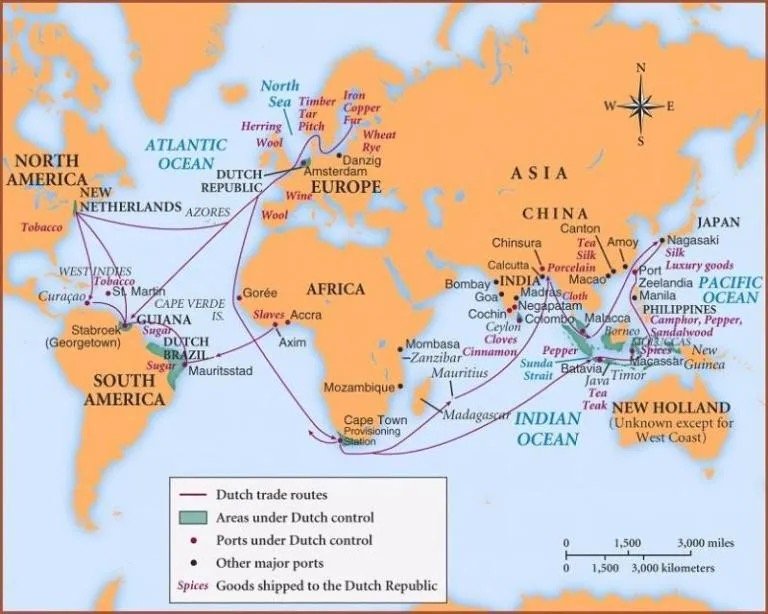

The city’s layout silently narrates the historical journey of the Spice Routes during the Dutch Golden Age (roughly 1588-1672), when the Netherlands dominated up to 50% of global trade. While sugar and spices were the focus of this first-ever global trade cartel, rum was created along the way. With its origins in Asia, sugarcane, rum’s base ingredient, would be transported to the Americas, and the social and economic structures of all in between would be upended.

The Dutch began sailing to the East Indies in 1595, trading in spices and locating their origins. Here, they found the native source of sugarcane in New Guinea. Sugar, though rare and expensive, was familiar to the Europeans, as they encountered it during the Crusades to the Middle East. Before the eighth century, India was the earliest known location where cane sugar was processed into crystals. By the eighth century, Arab and Muslim traders introduced sugar cane to the Mediterranean, specifically Cyprus and Crete. The locals did not want to grow and harvest the crop, so people from the Black Sea region (Slavs from Romania) were brought in as forced labor. Greeks, Turks, and eventually Africans would also be forced to work as enslaved people in harvesting sugarcane.

Map of Dutch Trade Routes

By 1619, Batavia (now Jakarta), on Java, became the center of the Dutch East Indies for over three centuries. From here, the Dutch East India Company (VOC) ran its massive military and trading empire, controlling the spice trade between Asia and Europe and creating inter-Asian trade networks where they acted as brokers and shippers. On Java, the Dutch first encountered “arrack,” an alcoholic drink distilled from sugarcane molasses and fermented red rice made by ethnic Chinese planters. For centuries, a fermented sugarcane spirit called “brum” had been established in nearby Malaysia. Both drinks likely owe their origins to the Arab and Muslim traders who introduced distilling to the region while trading in the spices of the area. Arak is the Arabic word for “sweat,” referring to the condensation during distillation. The word alcohol derives from the Arabic word “al-kohl.”

EAST INDIES TO WEST INDIES: SUGARCANE AND THE LARGEST SOCIAL AND COMMERCIAL EXPERIMENT

In looking at the map on the picnic table, I traced a finger from our location on Javastraat west and south, which mirrored the Dutch journey through India, where trading colonies were founded. When my finger reached Krugerstraat, symbolizing colonial Africa, I realized the Dutch had everything — crops from the East Indies, know-how from India, and enslaved labor from Africa — to create the world's most extensive sugar plantations in the West Indies and South America. Plotting a line from Transvaalbuurt to Westindsche Buurt represents the rounding of Cape of Good Hope and crossing of the Atlantic to where fortunes would be sought, and cultures from all along this route would come together to live in the most significant social and commercial experiment ever witnessed. Continuing north from Curaçaostraat to Stuyvesantstraat, it's evident New Amsterdam was a strategic stop for rest and conducting commerce with the English in Virginia and New England before heading east, ultimately returning to the central canals of Amsterdam and concluding the expedition (with astronomical profits).

RUM BARREL EXPERIENCE: EXCELLENT COCKTAILS, LAIDBACK

We finished our cocktails, and I folded the map. While Rum Barrel didn't provide me with an elaborate story I could unpack and reveal the Dutch history and connection to rum, it did offer an inviting, bright atmosphere. It transported me to the islands as I sipped on a Hemingway daiquiri and studied the map on the picnic table where the clues presented themselves. This was a first-class, top-notch rum bar with lots to choose from and excellent handcrafted cocktails. They aren’t looking to tell the story of Dutch colonial history, and that’s okay.

UNRAVELING THREADS: AMSTERDAM’S WEALTH AND RUM’S BIRTH

In the next part of the Rum Through the Tulips series, we will have a meal at Mama Makan Indonesia Kitchen, navigate some more streets of Amsterdam, and unravel how Amsterdam and its citizens became, by the mid-1600s, the wealthiest city and people in Europe (by far) while acting as the midwife at the birthing of rum (merely a side hustle at the time).

Author Owen Hyland founded Faraday West Indies Rum and lives in New Hampshire.